Introduction

Wars and rumors of wars. Daniel’s vision chronicles conflict after conflict, king after king, ruler after ruler. It is a truly prophetic vision—telling the events that are to occur on the political stage for the next several hundred years. The theme is the same as previous Daniel chapters: Nebuchadnezzar’s dream in chapter 2, the beasts of chapter 7, and the ram and goat of chapter 8. Daniel details the successive kingdoms, from the Persian Empire to the Roman Empire. It is a period of history which with most of us are unfamiliar—the black box of the biblical record—between Malachi and the New Testament, from 480 BC to 100 BC.

“The prophetic details of Chapter 11 are remarkable, particularly the sequence outlining the reign of the Greek kings and the intrigue and conflicts between the northern (Seleucid or Syrian) and the southern (Ptolemaic or Egyptian) kingdoms. So precise are the prophetic predictions that they draw criticism from skeptics like Porphyry who claimed that Daniel’s revelation was a forgery.” (G. Erik Brandt, The Book of Daniel: Writings and Prophecies, 313)

Daniel 11:1 in the first year of Darius the Mede, even I, stood to confirm and to strengthen him

Even though the text calls the ruling Persian king “Darius the Mede,” that individual is called “Cyrus the Great” by modern historians. The discrepancy has led some to disparage the historical accuracy of the Book of Daniel. Based on the chronology, they must be the same person. Based on the fact that Daniel was taken to Babylon as a young man in the years before the 589 destruction of Jerusalem, he is unlikely to have lived long enough to know any Persian ruler other than Cyrus the Great.

Daniel has been a witness to and ruler in the rise of the Persian Empire. A member of the king’s court under Nebuchadnezzar when the Babylonians were ruling, Daniel retained a position of influence among the Persians as this verse testifies. The Persian Empire was a big deal!

“The flower of western civilization burst into full bloom five centuries before the birth of Jesus Christ. Never before or since has an outpouring of cultural development on such a grand and far-reaching scale been realized on earth. It was, however, just as Charles Dickens said of Revolutionary France, the best of times and also the worst.

“On the eve of its golden age, Greece was in peril. Xerxes, king of kings and ruler of the Persian Empire, which stretched from the Indus River to the shores of the Mediterranean Sea, and from the Caucasus to the Indian Ocean, had turned his attention toward the Europeans who dared to resist his will.

“Persia was, in the truest sense, the greatest superpower of its day. Cyrus the Great launched the era of Persian expansion in the 6th century BC, and his successors held dominion of much of the known world for nearly three centuries. With Persia at the height of its glory, Xerxes ruled peoples of great diversity. Phoenicians, Egyptians, Medes, Cypriotes, Syrians, Levantines and Ethiopians were his subjects, as were those Greeks who had ventured forth from their mainland and established cities on the islands of the Aegean Sea, along the coasts of the Black Sea and Asia Minor.” (Michael E. Haskew, https://www.historynet.com/greco-persian-wars-xerxes-invasion.htm)

Daniel 11:2 there shall stand up yet three kings in Persia; and the fourth shall be far richer than they all

The four great Persian kings referenced are

· Cyrus the Great 559-530 BC

· Cambyses II 530-522 BC

· Darius I 522-486 BC

· Xerxes I 485-465 BC

About 100 years after Nebuchadnezzar conquered Jerusalem, Xerxes I ascended the Persian throne. As the scripture states, he was richer than the preceding three kings, having benefited from the taxation practices of Darius I. Still, in his own right, Xerxes was an ambitious conqueror and capable ruler, focusing his expansionist ambitions on the Greek city-states. When the Persians were finally beaten by the Greeks, Alexander the Great marveled at the wealth of the kingdom, accrued over 228 years.

“Tiridates led Alexander [the Great] into a large building behind the palace of Xerxes [at Persepolis] that served as both an armory for the royal bodyguard and a repository for the king’s wealth. Diffused light filtered through a series of openings in the roof above and washed gently over the tons of gold and silver bullion that had been neatly and methodically stored there. Within the treasury building were 120,000 talents of bullion, the largest single concentration of wealth to be found anywhere in the ancient world.

“Darius I had imposed a tribute of precious metals in addition to a tribute of goods on his satraps and on the subject nations of the empire. Instead of converting that tribute into coins that could then have been put into circulation, Darius and his successors had it melted and then formed into ingots of gold and silver. The bars were stored in the palace treasury, and when the kings of Persia needed to finance particular projects, wars, or adventures, the precious metals were cast into coins. It was Darius who had introduced the coining of money into the empire; hence, the Persian coin became known as the Daric. Until that time, the empire had been administered largely on the basis of barter.

“Successive generations of Persian kings had dipped into the treasury and spent vast sums on themselves. Over the years, they had spent great amounts on administering and expanding the empire and had dispensed large sums in fighting, hiring, and bribing the Greeks. Yet no matter how much money the kings spent, every year at the New Year ceremony more came in to replenish and add to the royal coffers. In the treasury building at Persepolis, Alexander was shown the full measure of how wealthy the Achaemenid kings of Persia had been and how wealthy he had now become. (John Prevas, Envy of the Gods, pp. 18-19)

Daniel 11:2 he shall stir up all against the realm of Grecia

“Xerxes the Great, was the fourth King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire, ruling from 486 to 465 BC. He was the son and successor of Darius the Great (r. 522 – 486 BC) and his mother was Atossa, a daughter of Cyrus the Great (r. 550 – 530 BC), the first Achaemenid king. Like his father and predecessor Darius I, he ruled the empire at its territorial apex.” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Xerxes_I )

“[Xerxes] resolved to succeed in Greece where his father had not. He instituted new taxes, which created revolts, none more so than in Babylon. The king responded with brute force, ordering his troops to sack the city, wreck the major temple, and melt down a large gold statue of the chief local god, Marduk, for the wealth that the gold would bring.

“Xerxes assembled an army and navy larger than his father had and invaded Greece, in 480 B.C. His invasion was notable for his method of transporting his troops across the Hellespont: He ordered more than 300 ships to be lined up side by side and then ordered built a bridge made of flax and papyrus. (Xerxes displayed his famous temper by, after being informed that the waters of the Hellespont had washed away one of the "pontoons," ordered the sea whipped for insubordination.) The army was so large that it took seven days and nights for all of them to cross. After an initial yet militarily expensive victory at the Battle of Thermopylae, Xerxes himself watched the Greeks outsail and destroy the Persian fleet at Salamis and then took a large part of his army home. The Persian army that stayed behind found itself defeated again, at the Battle of Plataea in 479 B.C.” (http://www.socialstudiesforkids.com/articles/worldhistory/xerxesthegreat.htm)

Daniel 11:3 a mighty king shall stand up, that shall rule with great dominion, and do according to his will

The Persian Empire dominated the Middle East from the conquest of Babylon in 559 BC until they were defeated by Alexander the Great in 331 BC. Daniel’s prophecies repeatedly reference Alexander the Great (Daniel 7:6; 8:5-8), specifically mentioning the division of his great empire upon is premature death. Again the unbeaten conqueror is “the mighty king… that shall rule with great dominion.” The Macedonian or Greek Empire began with Alexander’s conquests and represent the next great empire on the world stage.

Daniel 11:4 his kingdom shall be broken, and shall be divided toward the four winds

Alexander the Great died suddenly in 323 BC. No plans for a successor were in place, leaving a power vacuum that was filled by his generals and confidants. This left his great empire divided into four different domains—called the Diadochi, meaning “successors.” The Macedonian Empire then became divided between Ptolemy, Cassander, Lysichamus, and Seleucus.

“The vision foretold that Alexander’s expansive kingdom would not be given to his direct posterity, nor would his reign and dominion remain intact. These words were fulfilled with remarkable precision. No heir assumed the throne and the kingdom was broken into four smaller kingdoms.

“The kingdom eventually rested on four of his generals. Exercising their military and political might, they carved out major Greek kingdoms. Cassander, Ptolemy, Lysimachus, and Seleucus consolidated power from their rivals into four principal kingdoms: Greece, Thrace-Phrygia, Syria-Babylon, and Egypt.” (G. Erik Brandt, The Book of Daniel: Writings and Prophecies, 319)

Daniel 11:5-19 Seleucid Empire versus the Ptolemaic Empire

These verses speak of a king from the north battling a king from the south. The text is referring to multiple battles that happened over hundreds of years between the Seleucid Empire and the Ptolemaic Empire in Egypt, spanning the time period from 305 BC to 167 BC. These kingdoms are unfamiliar to most of us, but they span the gap in the Biblical record between Malachi and the New Testament.

From the perspective of Jerusalem, Egypt is south, ruled by the Macedonian descendants of Ptolemy, and Syria is north, ruled by the Seleucid family from the capital of Antioch or Seleucia (modern Bagdad). As always, Israel is inconveniently located between two world powers. We need to clarify that there is more than one king of the north and more than one king of the south. The text reads like the battles go back and forth between only two individuals, but they go back and forth between the successive kings of Seleucia and successive kings of the Ptolemaic dynasty. Modern historians refer to these conflicts as the Syrian Wars.

· First Syrian War (274-271 BC)

· Second Syrian War (260-253 BC)

· Third Syrian War (246-241 BC)

· Fourth Syrian War (219-217 BC)

· Fifth Syrian War (202-195 BC)

· Sixth Syrian War (170-168 BC)

In the mood for a history lesson? If not, then don’t worry about the king of the south and the king of the north.

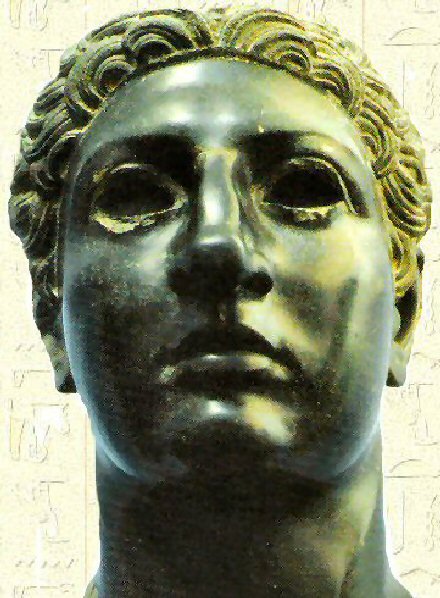

Daniel 11:5 the king of the south shall be strong

After Alexander the Great’s vast empire was divided up, Egypt came under the control of the Ptolemaic Dynast. Ptolemy I had been a companion of Alexander and was a trusted historian. With the division of the Empire, Ptolemy set his eyes on Egypt, hoping to rule there as the first Macedonian to rule Egypt directly. He was wise to adopt much of Egyptian history and religious practices in his rule. Although the Ptolemies definitely brought a Hellenistic influence to Egypt, Ptolemy wanted to acknowledge the religion and culture of the Egyptians—so he set himself up as Pharaoh as if he had been born and raised on the banks of the Nile.

The first big challenge to his authority came from Perdiccas who was a rival general of Alexander. Perdiccas invaded Greece but was routed by Ptolemy’s forces.

“Ptolemy's decision to defend the Nile against Perdiccas ended in fiasco for Perdiccas, with the loss of 2,000 men. This failure was a fatal blow to Perdiccas' reputation, and he was murdered in his tent by two of his subordinates. Ptolemy immediately crossed the Nile, to provide supplies to what had the day before been an enemy army. Ptolemy was offered the regency in place of Perdiccas; but he declined. Ptolemy was consistent in his policy of securing a power base, while never succumbing to the temptation of risking all to succeed Alexander.

“In the long wars that followed between the different Diadochi, Ptolemy's first goal was to hold Egypt securely.” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ptolemy_I_Soter)

Ptolemy I was the first of a series of kings in Egypt, all Macedonians ruling Egypt from within; collectively these rulers are referred to in Daniel 11 as “the king of the south,” as if they were just one person when in fact, the scripture has reference to Ptolemy I and his multiple successors, all named Ptolemy as well.

Daniel 11:6 the king’s daughter of the south shall come to the king of the north to make an agreement

Josephus tells us that Ptolemy I seized Jerusalem by treachery and deceit, taking thousands of Hebrew slaves back to Egypt (Antiquities of the Jews, Book XII, 1:1). His son, Ptolemy II, was kinder towards the Jews, even inviting an entourage to bring him a copy of the Law of Moses so that it could be translated from Hebrew into Greek for his library. At the time, the library of Alexandria Egypt was expanding to become the greatest library in ancient times.

In the First Syrian War against the Seleucids (276-272 BC), Ptolemy II seized control of the coastal towns of the eastern Mediterranean. In the Second Syrian War (260-253 BC), he lost some many of the territories gained. In order to form a political alliance, he offered his daughter Berenice to the Seleucid king, Antiochus II, fulfilling the prophecy that the “king’s daughter of the south shall come to the king of the north to make an agreement.” Other than Mary, the mother of the Son of God, where have you found a prophecy predicting the life of a woman in the scriptures? Berenice may be the only instance, and yet her story is almost completely unknown!

In 252 BC, Berenice travelled to Antioch with a huge dowry to marry Antiochus II. One of the stipulations of the arranged marriage was that Antiochus would have to divorce his first wife Laodice, with whom he already had two sons. So the first wife was sent off in exile and Berenice became the queen of the Seleucid Empire. By Antiochus, she bore a son who was set to become the rightful heir of the kingdom, but Laodice had other plans. A battle for power and posterity developed between competing wives, Berenice and Laodice.

“Within a year, Berenice had produced a son by Antiochus II, in whose person was the promise of a lasting peace between the Ptolemies and the Seleucids. Nevertheless, only a few months after the birth of this child, Antiochus abandoned Berenice and Antioch for Laodice and Ephesus. For the next five years, Berenice remained in Antioch, raising her son and hoping for the return of her husband. Indeed she had every reason to anticipate this return…

“Refusing to accept the total rejection of her and her sons which would result if Antiochus II returned to Berenice, Laodice had Antiochus II poisoned and her older son, Seleucus, proclaimed king. In order to save the Seleucid throne for her sons, Laodice bribed the appropriate officials in Antioch and orchestrated first the arrest and imprisonment of Berenice and her young son in a suburb of Antioch, and then the kidnapping and murder of Berenice’s son.” (Encyclopedia.com, “Berenice Syra”)

Laodice Berenice Syra

After the kidnapping and murder of her son, Berenice’s future was in question. She appealed to the people of Antioch for protection. Meanwhile, her brother, Ptolemy III, had by this time risen to the throne of Egypt. Full of rage and revenge at the murder of his nephew and repudiation of his sister, he launched an attack on the Seleucids to the north starting the Third Syrian War (246-241 BC) .

(The phrase “out of the branch of her roots” means literally from the descendants of her ancestor, or more simply, “a relative.” Ptolemy III was Berenice’s full brother, the one who would stand up in his estate and come with an army to the king of the north.)

“Ptolemy III Euergetes, decided to come to the aid of his sister. In September, he launched an attack on the Seleucid Empire. He first arrived in Seleucia in Pieria, where he was welcomed, then proceeded to Antioch, where he was also received with enthusiasm, if the papyrus that reports this reception should not be dismissed as propaganda. Berenice, however, was so stupid as to leave her safe haven and was instantly killed; a sign that public opinion was not as favorable to Berenice as the pro-Ptolemaic sources suggest. According to this papyrus, Berenice was still alive when Ptolemy arrived, but this is probably untrue…

“Several sources tell us that Ptolemy made a grand campaign into the interior of the Seleucid Empire and even conquered it completely.” (https://www.livius.org/sources/content/mesopotamian-chronicles-content/bchp-11-invasion-of-ptolemy-iii-chronicle/)

Daniel 11:8 he shall also carry captives into Egypt their gods… and with their precious vessels of silver and of gold

This verse could be rendered more plainly, “And he shall bring back to Egypt the captured idols with their precious vessels of gold and silver.” In the Third Syrian War, when Ptolemy III drove his forces deep into the Seleucid Empire, he took back artifacts previously plundered from Egypt by the Persians.

“The king is also credited for recovering, during one of his campaigns abroad (the Third Syrian War), some of the sacred statues that the Persians had carried off during their rule of Egypt. Like his father, Ptolemy III's reign of 25 years saw Egypt prosper and expand. He continued the work of his father and grandfather in Alexandria, particularly at the Great Library.” (http://www.touregypt.net/featurestories/ptolemyiii.htm)

His popularity in Egypt was bolstered by his attention to detail in returning with hundreds of statues and artifacts plundered by the Persian King Cambyses. The Egyptians called him Ptolemy Euegertes, meaning “benefactor.”

“They took care of the statues of the gods, which had been robbed by the barbarians of the land Persia from temples of Egypt, since His Majesty had won them back in his campaign against the two lands of Asia, he brought them to Egypt, and placed them on their places in the temples, where they had previously stood.” (“Canopus Decree,” English translation by S. Birch, text: Cairo CG 22187)

Daniel 11:10-11 his sons shall be stirred up, and shall assemble a multitude of great forces

Seleuca II had two sons, Seleuca III and Antioch III. Successors of their father, they are two kings of the north stirred up to action by a crumbling geo-political scene. Seleuca III went to work shoring up rebellions in the west but would be killed in battle leaving Antioch III, later called Antioch the Great, to avenge losses in the south. Ascending to power in 222 BC, he took his armies along the Palestinian coast towards Egypt, moving methodically in taking the port cities one at a time. After his brother’s death, Antiochus was the sole recognized ruler in the Seleucid Empire.

“Antiochus was now free to conduct what has been called the Fourth Syrian War (219-216), during which he gained control of the important eastern Mediterranean sea ports of Seleucia-in-Pieria, Tyre, and Ptolemais. In 218 he held Coele Syria (Lebanon), Palestine, and Phoenicia. In 217 he engaged an army (numbering 75,000) of Ptolemy IV Philopator, a pharaoh of the Hellenistic dynasty ruling Egypt, at Raphia, the southernmost city in Syria. His own troops numbered 68,000. Though he succeeded in routing the left wing of the Egyptian army, his phalanx (heavily armed infantry in close ranks) in the centre was defeated by a newly formed Egyptian phalanx. In the subsequent peace settlement, Antiochus gave up all his conquests except the city of Seleucia-in-Pieria. (See Syria, history of.)” http://homepages.rpi.edu/~holmes/Hobbies/Genealogy2/ps22/ps22_431.htm

As described in Daniel 11:11, “the king of the south,” this time meaning Ptolemy IV, gathered his army and headed north to meet Antiochus. The Fourth Syrian War between Antioch III and Ptolemy IV was a battle that took place on the Palestinian coast. While not the most important battle in the history of the Middle East, the armies were huge and the consequences significant if you lived in Jerusalem. The political climate in Jerusalem at the time was divided, some favoring victory by the Seleucids, others preferring the Ptolemies. Israel found itself the inconvenient battlefield of the king of the north and the king of the south. It was no picnic; Josephus lamented, “the Jews, as well as the in habitants of Coelesyria suffered greatly, and their land was sorely harassed… while he (Antiochus the Great) was at war with Ptolemy Philopater.” (Antiquities, Book XII, 3:3) Of the two competing dynasties, the Seleucids were probably more generous benefactors. Contrary to the days of King David, nobody in Jerusalem had the strength militarily to defend the Jews from their more powerful neighbors.

Western historians records Ptolemy IV as the winner of the Fourth Syrian War, but it was more of a stalemate. In contrast, Josephus declared Antiochus the winner; Antiochus had obtained control of northern Palestine and Syria, establishing himself as a legitimate and powerful ruler. Ptolemy IV (Philopater) had no further ambitions during his reign.

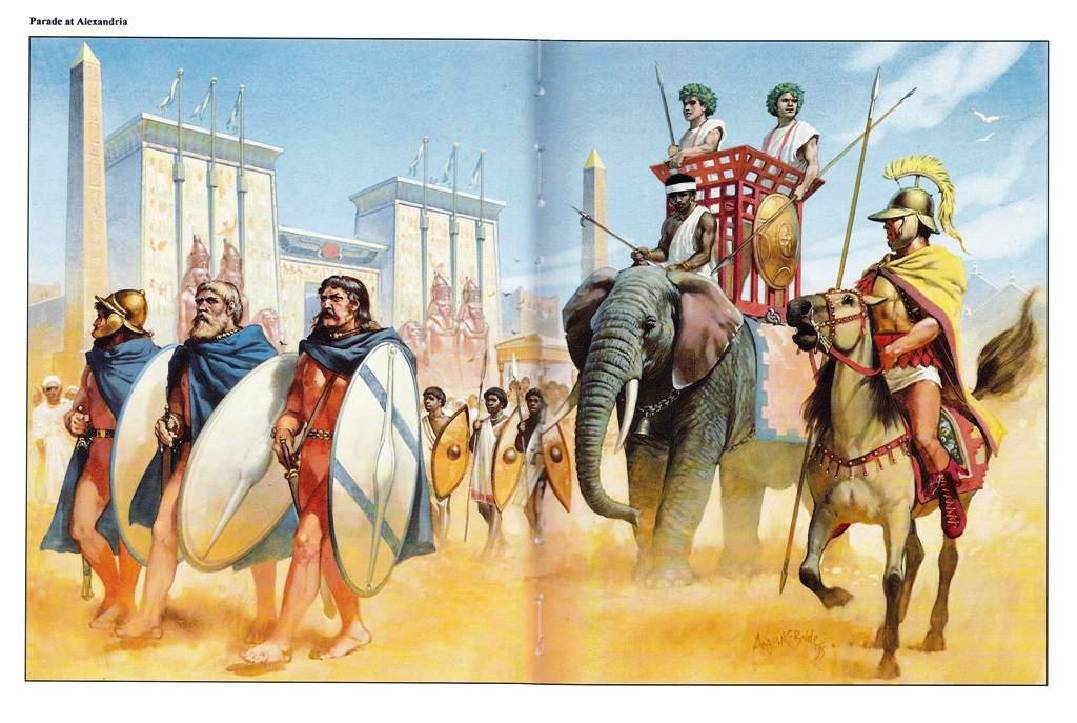

Military historians record the common use of elephants in the battles of Alexander the Great and the Syrian Wars. Both Asian and African elephants were used to intimidate and trample the enemy.

Daniel 11:13 For the king of the north shall return, and shall set forth a multitude greater than the former

In the see-saw battle for the land of Palestine, the pattern was a war for every generation. After each Syrian war, the battle lines were drawn, and treaties were made. However, these treaties only were considered valid during the lifetime of the respective kings. So every new king, it seems, takes it upon himself to avenge the losses of the last Syrian War. This happened again after Ptolemy IV died and his son took power. An Egyptian army under general Scopas led his armies to battle yet again, prompting “the king of the north” (still Antiochus III or Antiochus the Great) to return, setting “forth a multitude greater than the former.” This would be the Fifth Syrian War.

Josephus

But at length, when Antiochus had beaten Ptolemy, he seized upon Judea: and when Philopater (Ptolemy IV) was dead, his son sent out a great army under Scopas, the general of his forces, against the inhabitants of Coelesyria, who took many of their cities, and in particular our nation; which, when he fell upon them, went over to him. Yet was it not long afterward when Antiochus overcame Scopas, in a battle fought at the fountains of Jordan, and destroyed a great part of his army. But afterward, when Antiochus subdued those cities of Coelesyria which Scopas had gotten into his possession, and Samaria with them, the Jews, of their own accord went over to him, and receive him (Antiochus) into the city and gave plentiful provisions to all his army, and to his elephants, and readily assisted when he besieged the garrison which was in the citadel of Jerusalem. Wherefore Antiochus thought it but just to requite the Jews’ diligence and zeal in this service: so he wrote to the generals of his armies, and to his friends, and gave testimony to the good behavior of the Jews toward him. (Antiquities of the Jews, Book XII, 3:3)

Daniel 11:14 there shall many stand up against the king of the south

The Ptolemaic dynasty had been stable for the most part. It is remarkable that a Macedonian family could have successfully ruled in Egypt without engendering nationalistic revolt among the Egyptians. They had been successful in doing so by honoring Egyptian religion and culture, fostering support of the temple priests. However, under the weak rule of Ptolemy IV, Egyptian nationalism was brewing and the Ptolemies began to lose their grip on Egypt.

“A revolt had broken out in Upper Egypt… in the last years of Ptolemy IV's reign and Thebes had been lost in November 205 BC, shortly before his death. The conflict continued throughout the infighting of Ptolemy V's early reign and during the Fifth Syrian War.

“Shortly after this, Ptolemy V launched a massive southern campaign, besieging Abydos in August 199 BC and regaining Thebes from late 199 BC until early 198 BC. The next year, however, a second group of rebels in the Nile Delta... captured the city of Lycopolis near Busiris and invested themselves there. After a siege, Ptolemy's forces regained control of the city. The rebel leaders were taken to Memphis and publicly executed on 26 March 196 BC, during the feast celebrating Ptolemy V's coronation as Pharaoh.” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ptolemy_V_Epiphanes)

For twenty years, from 205 BC to 185 BC, internal conflict plagued Egypt. Egyptian nationalist rebels fought against Ptolemy V and his forces in various cities and regions of Egypt. The internal rebellion took a nagging toll on Ptolemy V. In search of peace:

“Ptolemy V issued the 'Amnesty Decree', which required all fugitives and refugees to return to their homes and pardoned them for any crimes committed before September 186 BC (except temple robbery). This was intended to restore land to cultivation that had been abandoned during the prolonged period of warfare. To prevent further revolts in the south, a new military governorship of Upper Egypt… Greek soldiers were settled in villages and cities in the south, to act as a garrison force in the event of further unrest.

“The rebels in Lower Egypt still continued to fight on. In 185 BC, the general Polycrates of Argos succeeded in suppressing the rebellion. He promised the leaders of the rebellion that they would be treated generously if they surrendered. Trusting this, they voluntarily went to Sais in October 185 BC, where they were stripped naked, forced to drag carts through the city, and then tortured to death. Whether Polycrates or Ptolemy was responsible for this duplicitous cruelty is disputed.” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ptolemy_V_Epiphanes)

Daniel 11:15-16 his chosen people… in the glorious land

The terms “chosen people” and “glorious land” refer to the Jews and the land of Judea. Antiochus III had established himself as the ruler of the Jewish nation, and there was nothing that the Jews could do about it. There was no king David to fight off the enemy. There was nobody who could stand up to Antiochus, so the Jews made peace with him. Much has been written about Greek influence on Judaism. In good measure, the Hellenization of the Jews begins at this time period.

Daniel 11:17 he shall give him the daughter of women, corrupting her

“Problems at home led Ptolemy to seek a quick and disadvantageous conclusion. The nativist movement, which began before the war with the Egyptian Revolt and expanded with the support of Egyptian priests, created turmoil and sedition throughout the kingdom. Economic troubles led the Ptolemaic government to increase taxation, which in turn fed the nationalist fire. In order to focus on the home front, Ptolemy signed a conciliatory treaty with Antiochus in 195 BC, leaving the Seleucid king in possession of Coele-Syria and agreeing to marry Antiochus' daughter Cleopatra I.” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Syrian_Wars)

At this time, Antiochus was in a position of power. He probably could have conquered Egypt if he wanted to. However, the Romans began to be an important player on the world stage. They were interested in preserving stability in Egypt since the Egyptian farms were a source of imported grains. They put pressure on Antiochus to make peace with Egypt. “In response, Antiochus III indicated his willingness to make peace with Ptolemy V and to have his daughter Cleopatra I marry Ptolemy V. They were betrothed in 195 BC and their marriage took place in 193 BC in Raphia. At that time Ptolemy V was about 16 years and Cleopatra I about 10 years old.” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cleopatra_I_Syra)

Antiochus daughter became known as Cleopatra Syra or Cleopatra I. The text speaks of Ptolemy “corrupting her” likely because she was so young when she was betrothed to Ptolemy. She was the first of a line of Cleopatras who reigned as ruler in Egypt. The famous Cleopatra, the consort of Mark Antony and player on the world stage in the early days of the Roman Empire, was Cleopatra VII. For the next several generations, every Ptolemaic ruler is named Ptolemy or Cleopatra, depending on their gender.

Daniel 11:18 After this shall he turn his face unto the isles and take many

In Daniel 11, we have recounted one Syrian War after another. In fact, Antiochus III had just won the Fifth Syrian War (202-195 BC) when he gave up his daughter to wed Ptolemy V. In a shift, the text is going to talk about a war that was not between the king of the north and the king of the south; it is the Roman-Seleucid War between the king of the north, Antiochus III, and the Romans to the west.

At the time Greece was divided into three big players, the Aetolians, the Achaeans, and the Macedonians. The conflict began in 192 BC when Antiochus III was invited by the Aetolians (central Greece) to help them battle the Macedonians (northern Greece) and counter a growing Roman influence in the region. Their first object was the city of Larissa, in Macedonia. Antiochus was more than happy to oblige but received less help from the Aetolians than he had hoped. However, the Romans were worried about Seleucid influence in Greece and mobilized to meet Antiochus at Larissa. Antiochus backed off only to meet the Romans later at the battle of Thermopylae, where he was defeated.

The conflict also involved the Seleucid Navy. Antiochus had his navy mobilized quickly taking the isles of Rhodes, Samos, Colophon, and Phocea during the early stages of the war (see Gill’s Exposition of the Bible); thus fulfilling the prophecy of Daniel that he would turn his face to the isles and take many. Yet his control of these islands would not last. Eventually, Antiochus was beaten by the Romans—on land at the battle of Thermopylae and the battle of Magnesia—and at sea at the battle of Myonnesus. In capitulation, Antiochus was forced to sue for peace in 188 BC with the Peace of Apamea at the price of thousands of talents in reparations.

While it is unclear who the prince is mentioned in this verse, the idea that Antiochus’ plans to vanquish turned on him as he was soundly defeated. This fits the text’s reference to a reproach that would turn back upon him. He had gone from vanquisher to vanquished.

Daniel 11:19 he shall turn his face toward the fort of his own land

The losses to the Romans threatened Antiochus power at home. He started out thinking he would come to the Aetolians as liberator and increase his influence in the Greek isles. Instead, his army and navy had been defeated. He fled east at some risk of losing his control of his own kingdom. Fortunately for him, the Romans were not interested in chasing him down by sending their armies into Asia. They were happy to have driven Antiochus out of the Aegean.

Daniel 11:20 Then shall stand up in his estate a raiser of taxes in the glory of the kingdom

After Antiochus III’s death in 187 BC, his son Seleucus IV Philopater ascended to the throne (187-175 BC). The Peace of Apamea, required the Seleucids to pay war reparations of a great amount. Seleucus IV needed money to pay the debt. He entrusted a man named Heliodorus to raise the funds. The third chapter of 2 Maccabees in the Catholic Bible recounts what happened—how Seleucus found out about the Jewish Temple monies, how Heliodorus was sent to get them, and how he was rebuffed by a miracle in the Temple. Heliodorus is the “raiser of taxes in the glory of the kingdom.”

…a certain Simon, of the priestly clan of Bilgah, who had been appointed superintendent of the temple, had a quarrel with the high priest about the administration of the city market.

Since he could not prevail against Onias, he went to Apollonius of Tarsus, who at that time was governor of Coelesyria and Phoenicia,

and reported to him that the treasury in Jerusalem was full of such untold riches that the sum total of the assets was past counting and that since they did not belong to the account of the sacrifices, it would be possible for them to fall under the authority of the king.

When Apollonius had an audience with the king (Seleucus IV Philopater), he informed him about the riches that had been reported to him. The king chose his chief minister Heliodorus and sent him with instructions to seize those riches.

So Heliodorus immediately set out on his journey, ostensibly to visit the cities of Coelesyria and Phoenicia, but in reality to carry out the king’s purpose.

When he arrived in Jerusalem and had been graciously received by the high priest of the city, he told him about the information that had been given, and explained the reason for his presence, and he inquired if these things were really true.

The high priest explained that there were deposits for widows and orphans… Contrary to the misrepresentations of the impious Simon, the total amounted only to four hundred talents of silver and two hundred of gold.

It was utterly unthinkable to defraud those who had placed their trust in the sanctity of the place and in the sacred inviolability of a temple venerated all over the world.

But Heliodorus, because of the orders he had from the king, said that in any case this money must be confiscated for the royal treasury.

So on the day he had set he went in to take an inventory of the funds. There was no little anguish throughout the city.

Priests prostrated themselves before the altar in their priestly robes, and called toward heaven for the one who had given the law about deposits to keep the deposits safe for those who had made them.

Whoever saw the appearance of the high priest was pierced to the heart, for the changed complexion of his face revealed his mental anguish.

…It was pitiful to see the populace prostrate everywhere and the high priest full of dread and anguish.

While they were imploring the almighty Lord to keep the deposits safe and secure for those who had placed them in trust,

But just as Heliodorus was arriving at the treasury with his bodyguards, the Lord of spirits and all authority produced an apparition so great that those who had been bold enough to accompany Heliodorus were panic-stricken at God’s power and fainted away in terror.

There appeared to them a richly caparisoned horse, mounted by a fearsome rider. Charging furiously, the horse attacked Heliodorus with its front hooves. The rider was seen wearing golden armor.

Then two other young men, remarkably strong, strikingly handsome, and splendidly attired, appeared before him. Standing on each side of him, they flogged him unceasingly, inflicting innumerable blows.

Suddenly he fell to the ground, enveloped in great darkness. His men picked him up and laid him on a stretcher.

They carried away helpless the man who a moment before had entered that treasury under arms with a great retinue and his whole bodyguard. They clearly recognized the sovereign power of God.

As Heliodorus lay speechless because of God’s action and deprived of any hope of recovery,

the people praised the Lord who had marvelously glorified his own place; and the temple, charged so shortly before with fear and commotion, was filled with joy and gladness, now that the almighty Lord had appeared.

Quickly some of the companions of Heliodorus begged Onias to call upon the Most High to spare the life of one who was about to breathe his last.

The high priest, suspecting that the king might think that Heliodorus had suffered some foul play at the hands of the Jews, offered a sacrifice for the man’s recovery.

While the high priest was offering the sacrifice of atonement, the same young men dressed in the same clothing again appeared and stood before Heliodorus. “Be very grateful to the high priest Onias,” they told him. “It is for his sake that the Lord has spared your life.

Since you have been scourged by Heaven, proclaim to all God’s great power.” When they had said this, they disappeared.

After Heliodorus had offered a sacrifice to the Lord and made most solemn vows to the one who had spared his life, he bade Onias farewell, and returned with his soldiers to the king.

Before all he gave witness to the deeds of the most high God that he had seen with his own eyes.

When the king asked Heliodorus what sort of person would be suitable to be sent to Jerusalem next, he answered:

“If you have an enemy or one who is plotting against the government, send him there, and you will get him back with a flogging, if indeed he survives at all; for there is certainly some divine power about the place.

The one whose dwelling is in heaven watches over that place and protects it, and strikes down and destroys those who come to harm it.”

This was how the matter concerning Heliodorus and the preservation of the treasury turned out. (2 Maccabees 3:4-40)

As the text says, Heliodorus “was destroyed, neither in anger, nor in battle.” While the text says he was destroyed, it means not that he was killed but that his power was destroyed before the power of God. Heliodorus himself was forced to admit that God protects the temple, “and strikes down and destroys those who come to harm it.”

Daniel 11:21 And in his estate shall stand up a vile person… and obtain the kingdom by flatteries

The “vile person” spoken of was Antiochus IV Epiphanes. He “was a son of Antiochus the Great, and, after the murder of his brother Seleucus, took possession of the Syrian throne (175 BC) which rightly belonged to his nephew Demetrius. This Antiochus is styled in rabbinical sources, ‘the wicked.’ Abundant information is extant concerning the character of this monarch, who exercised great influence upon Jewish history and the development of the Jewish religion. Since Jewish and heathen sources agree in their characterization of him, their portrayal is evidently correct. Antiochus combined in himself the worst faults of the Greeks and the Romans, and but very few of their good qualities. He was vainglorious and fond of display to the verge of eccentricity, liberal to extravagance; his sojourn in Rome had taught him how to captivate the common people with an appearance of geniality, but in his heart he had all a cruel tyrant's contempt for his fellow men.” (http://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/1589-antiochus-iv-epiphanes)

All of these Syrian Wars have been leading up to the climax of Daniel’s prophecy—the acts of Antiochus IV Epiphanes. He gets more of the text and more of our attention for his role in the defilement of the temple and the First Abomination of Desolation in 168 BC.

Daniel 11:22-24 Antiochus IV Epiphanes rise to power

These verses chronicle Antiochus’ political machinations in solidifying his power base. While the historical record fails us, it seems that Antiochus had no qualms making great promises in treaties at home and with the Jews. It seems, his conscience was never bothered by deceitfully turning from old promises. Covenants, for a wicked man, can be kept or broken, depending on personal convenience.

Daniel 11:22 they… shall be broken; yea, also the prince of the covenant

“The ‘prince of the covenant’ (Dan. 11:22) referred to the Jewish religious leader or the high priest, Onias III. He was pious and loyal to the Mosaic practices and did not advocate the pagan elements of Hellenism (2 Mac. 3:5). As mentioned, he resisted Simon’s petition to be market commissioner (Agoranomos), who in revenge went to the Syrian officials informing them about the treasure in the temple. Heliodorus’s failure to retrieve the treasure placed Onias III out of favor with the Seleucid authorities. ‘When Antiochus IV ascended the throne (175 B.C.), [Onias] was summoned ot Antioch, and his brother Jason was appointed high priest in his place, having apparently promised a large sum of money for the appointment’ (2 Mac. 4:7-8). Jason, a strong proponent of Hellenism, built a Gymnasium in Jerusalem (2 Mac. 4:9). Three years later Menelaus, not a descendant of Aaron (2 Mac. 4:26), obtained the appointment by paying a larger sum of money. He was also a staunch advocate of Hellenism and continued the transformation of Jewish society away from their Mosaic roots. Menelaus, aided by the royal governor Andronicus, secretly had Onias assassinated in defiance of his oath of office (2 Mac 4:29-39). He represented a ‘break’ in the ancestral line of Aaron and the religious leadership of Judah.” (G. Erik Brandt, The Book of Daniel: Writings and Prophecies, 340-341)

“Breaking” the genealogical line of the prince of the covenant is a big deal. Jason taking office marks the break in the high priest office descending from the lineage of Aaron. “And no man taketh this honor upon himself, but he that is called of God, as was Aaron” (Heb. 5:4). Menelaus took the honor of high priest on himself without being a descendent of the Levites! How could he dare claim the office of High Priest? How could he bribe his way into the office without angering God? How could the office of high priest in the Temple be respected? In Christ’s day, the high priesthood was still an appointment of Herod rather than a calling of God. It all started with Jason’s blasphemous ministry without the keys of the priesthood; this break represents a clear move toward apostasy.

Daniel 11:24 he shall do that which his fathers have not done, nor his father’s fathers

Antiochus IV was somewhat of an embarrassment to the respectable Seleucids. He liked to pretend he wasn’t king so he could frolic with the common people, carousing with the young men as if he hadn’t a care in the world. He earned the nickname Antiochus Epimanes (meaning “madman”), a play on his title Epiphanes (meaning the manifestation of God). To the Jews, his title was blasphemy, and his behavior was an abomination as he was particularly devoted to the idolatry of the empire.

“In regard to public sacrifices and the honours paid to the gods, he surpassed all his predecessors on the throne; as witness the Olympium at Athens and the statues placed round the altar at Delos. He also used to bathe in the public baths, when they were full of the townspeople, pots of the most expensive unguents being brought in for him; and on one occasion on some one saying, ‘Lucky fellows you kings, to use such things and smell so sweet!’ without saying a word to the man, he waited till he was bathing the next day, and then coming into the bath caused a pot of the largest size and of the most costly kind of unguent called stacte to be poured over his head, so that there was a general rush of the bathers to roll themselves in it; and when they all tumbled down, the king himself among them from its stickiness, there was loud laughter.” (Polybius, Histories, Book 26:1)

Daniel 11:25 The Sixth Syrian War

The Sixth Syrian War began amidst weakness at the top of both the Egyptian and the Syrian kingdoms. Ptolemy Philometor and his brother Ptolemy Physcom were ostensibly co-pharaohs, but two older advisors were really running the show. Eulaeus and Lenaeus, the power behind the scenes, planned for war with the misguided expectation that Antiochus IV Epiphanes would be too weak to respond, but they underestimated the madman. Antiochus took the initiative and invaded Egypt in 170-169 BC. He took the frontier city of Pelusium, then Memphis in southern Egypt, even capturing the older of the two brother-kings, Ptolemy Philometor. In control of southern Egypt, Antiochus treated his captive king very well, and convinced Philometor that his real goal was to take over Alexandria and put him in charge of all of Egypt by displacing his brother from Alexandria. At the time the Egyptian populace was divided between the Ptolemy brothers, the Alexandrians favoring the younger Physcom.

Physcom dispatched some “neutral” Greek envoys to put an end to the aggression, but Antiochus rejected the Egyptian claim to Coele-Syria via the dowry of Cleopatra and declared that the area had been the historic domain of the Seleucids. Rejecting the peace envoy, Antiochus proceeded all the way to Alexandria and laid siege to the city. Frustrated with his inability to tighten the siege and overtake Alexandria, he returned home hoping that Ptolemy Philometor would continue the siege as a civil war—pitting brother against brother.

Within a year (168 BC), the brothers were reconciled and Antiochus tried again, invading Egypt and sending his navy to take over Cyprus. These aggressive moves were against the Peace of Apamea in which his father had been bested by the Romans, required to pay huge war reparations, and forbidden to build up a navy. The Roman Senate sent one of their commanders to Antiochus to demand an end to the war. By this time Antiochus had again gained control of all of Egypt but Alexandria, but when the Roman commander Polipius demanded Antiochus desist and return to Syria, Antiochus was forced to return home with his tail between his legs.

“When Antiochus had advanced to attack Ptolemy in order to possess himself of Pelusium, he was met by the Roman commander Gaius Popilius Laenas. Upon the king greeting him from some distance, and holding out his right hand to him, Popilius answered by holding out the tablets which contained the decree of the Senate, and bade Antiochus read that first: not thinking it right, I suppose, to give the usual sign of friendship until he knew the mind of the recipient, whether he were to be regarded as a friend or foe. On the king, after reading the despatch, saying that he desired to consult with his friends on the situation, Popilius did a thing which was looked upon as exceedingly overbearing and insolent. Happening to have a vine stick in his hand, he drew a circle round Antiochus with it, and ordered him to give his answer to the letter before he stepped out of that circumference. The king was taken aback by this haughty proceeding. After a brief interval of embarrassed silence, he replied that he would do whatever the Romans demanded. Then Popilius and his colleagues shook him by the hand, and one and all greeted him with warmth. The contents of the despatch was an order to put an end to the war with Ptolemy at once. Accordingly a stated number of days was allowed him, within which he withdrew his army into Syria, in high dudgeon indeed, and groaning in spirit, but yielding to the necessities of the time.” (Polybius Histories, Book 29, section 27; http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.01.0234%3Abook%3D29%3Achapter%3D27 )

Daniel 11:29 He shall return into his land with great riches; and his heart shall be against the holy covenant

Between his first and second invasions of Egypt, Antiochus returned home. He wouldn’t act against the Jews until after the second invasion, but news from Jerusalem fueled his anger.

“A very unfortunate occurrence for the Jews took place towards the end of the war. Rumors circulated in Jerusalem that Antiochus had died in battle. Jason, of the Hasmonean Dynasty and the ousted high priest family, immediately raised an army of a thousand men and retook is position at the temple. Menelaus, initially held up in his castle, escaped and fled to Antiochus to report the uprising at Jerusalem. Many of the remaining Jews believed the city had been liberated. Celebrations broke out among a portion of the population. When the king heard the news, he was enraged.” (G. Erik Brandt, The Book of Daniel: Writings and Prophecies, 344)

Daniel 11:30 the ships of Chittim shall come against him

During Antiochus’ second invasion of Egypt, he sent his navy against the island of Cyprus. Chittim, in this instance, must reference Cyprus. The Romans were not happy with Antiochus’ building up his navy against the decrees of the Peace of Apamea. They sent a flotilla which destroyed Antiochus’ navy. So it wasn’t really the navy of Cyprus that ruined everything for Antiochus but the ships of Rome. Spurned and defeated after his second invasion of Egypt, Antiochus turned his anger upon the Jews, “he shall be grieved and return, and have indignation against the holy covenant.”

Daniel 11:31 they shall pollute the sanctuary of strength, and shall take away the daily sacrifice

Daniel prophesied of a future enemy of Israel, that…

…by him the daily sacrifice was taken away, and the place of his sanctuary was cast down.

And an host was given him against the daily sacrifice by reason of transgression and it cast down the truth to the ground; and it practiced, and prospered.

Then I heard one saint speaking, and another saint said unto that certain saint which spake, How long shall be the vision concerning the daily sacrifice, and the transgression of desolation, to give both the sanctuary and the host to be trodden under foot? (Dan 8:11-14, see also Dan. 8:23-26)

“On his return to Antioch, Antiochus became weighed down with depression and anger. Unable to vent his fury on Eypt, he would turn his displeasure against Jerusalem and Judah. In a blatant display of unbridled resentment and knowing there would be no outward retribution, Antiochus moved his army into the holy land. Fueled by the humiliating events at Alexandria, he lost all patience with the Jews and their religion. He vowed revenge because of their previous insolence. He and his army stopped at Jerusalem to ‘have intelligence, or [gain alliances] with them that forsake the holy covenant’ (Danl. 11:30). With the help of Jewish secularists, favorable to Hellenism, he entered the city in an act of reprisal and opened a period of severe persecution against those who would be true to Jehovah and the Mosaic religion.” (G. Erik Brandt, The Book of Daniel: Writings and Prophecies, 347)

“A royal decree proclaimed the abolition of the Jewish mode of worship; Sabbaths and festivals were not to be observed; circumcision was not to be performed; the sacred books were to be surrendered and the Jews were compelled to offer sacrifices to the idols that had been erected. The officers charged with carrying out these commands did so with great rigor; a veritable inquisition was established with monthly sessions for investigation. The possession of a sacred book or the performance of the rite of circumcision was punished with death.” (http://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/1589-antiochus-iv-epiphanes)

Josephus

…he left the temple bare, and took away the golden candlesticks, and the golden altar [of incense,] and table [of showbread,] and the altar [of burnt-offering;] and did not abstain from even the veils, which were made of fine linen and scarlet. He also emptied it of its secret treasures, and left nothing at all remaining; and by this means cast the Jews into great lamentation, for he forbade them to offer those daily sacrifices which they used to offer to God, according to the law… and when the king had built an idol altar upon God‘s altar, he slew swine upon it, and so offered a sacrifice neither according to the law, nor the Jewish religious worship in that country. He also compelled them to forsake the worship which they paid their own God, and to adore those whom he took to be gods; and made them build temples, and raise idol altars, in every city and village, and offer swine upon them every day.

For Antiochus to sacrifice swine upon the altar of God was an unthinkable desecration—an abomination of epic proportions. For three years, the Temple service was interrupted. Eventually, a small band of warriors, led by Judas Maccabees, defeated the larger Seleucid Army and re-established temple worship (celebrated annually as Hannukah). This desecration by Antiochus IV was the First Abomination of Desolation.

(Not the most accurate picture: the guards are in Roman dress not in Seleucid dress and the altar was much bigger, but the atrocity deserves a picture!)

Daniel 11:32-33 the people that do know their God shall be strong, and do exploits

The Maccabean family revolted from the reign of Antiochus, refusing to offer sacrifice to false gods, gathering the believers to them in the wilderness to organize a revolt. They were helped by God in several battles (exploits) with Seleucid armies to overcome the wickedness of Antiochus. They knew their God and were strong, while many of the Temple officials were leaning toward the worldliness of Greek culture. During the two years of external oppression, there were many Jews who remained faithful, but as Daniel prophesied, many lost their lives, “they that understand… shall instruct many: yet they shall fall by the sword and by flame, by captivity, and by spoil.”

Josephus

And indeed many Jews there were who complied with the king [Antiochus’] commands, either voluntarily, or out of fear of penalty that was denounced: but the best men, and those of the noblest souls, did not regard him, but did pay a greater respect to the customs of their country than concern as to the punishment which he threatened to the disobedient; on which account they every day underwent great miseries and bitter torments; for they were whipped with rods, and their bodies were torn to pieces, and were crucified while they were still alive and breathed.” (Antiquities of the Jews, Book XII, 5:4)

Daniel 11:36-39 The Idolatry of Antiochus

Secular histories don’t describe the mind of Antiochus with respect to idolatry. From Daniel, we learn that he intended not only to believe but to advance Seleucid polytheism, which was a modification of the more well-known gods of Greek mythology. His wickedness was greater than his fathers. While blasphemy against Jehovah was in his lips, he worshipped a new god, the god of forces, perhaps a god of military might and power. His religion was the religion of the anti-Christ. His attack on the holy temple and the covenant people qualifies him for this unflattering designation.

Daniel 11:40-44 Antiochus or Latter-day Anti-Christ

Scholars argue over this section of Daniel 11. Are they speaking of Antiochus again or is this a latter-day figure? The verses sound like they describe again the events of the Sixth Syrian War. Is Daniel merely recapitulating the conflict between Antiochus IV and the Ptolemy brothers? He bypassed lands east of the Jordan (v. 41), took nearly all of Egypt (v. 42), spoiled Egyptian wealth and threatened the borders of Libya and Ethiopia (v. 43), and was scared off by the Romans (v. 44).

Or, as the first of v. 40 intimates, is this an “end of the world” event? The phrase “at the time of the end” might suggest an apocalyptic anti-Christ attending the final conflict between good and evil. However, since other Daniel verses speak of “the end” in reference to a specific time period other than the latter-days (see Daniel 8:17-18; 11:27-28), the authors suggest the former interpretation.