Jeremiah 34:1 The word which came… when Nebuchadnezzar… fought against Jerusalem

Again, Jerusalem is under Babylonian siege for an 18 month span, from 10th month of the 9th year of Zedekiah to the 4th month of the 11th year of Zedekiah. During this time period, probably the last few months, comes this prophecy from Jeremiah. Let’s assume that the city has been under siege for about a year. It makes sense that the Jews are starting to get nervous. They are working hard to keep the Babylonians outside the walls of the city but they know that they can’t hold them off forever. The soldiers and the king must be wondering, “What is going to happen to us when the Babylonians breach the walls?”

This prophecy is Lord giving an answer to Zedekiah, “they will burn the city and take you captive to Babylon.”

Jeremiah 34:5 But thou shalt die in peace: and with the burnings of thy fathers, the former kings which were before thee

Death would be too merciful for Zedekiah. When the Lord says he will “die in peace,” He means he will not die a violent death at the hands of the Babylonians. Such an end would be too good for him. Instead, the Lord is going to preserve him in a state of blindness so that he can think on the tragedy that occurred during his reign as king. He would be the last king of Israel until Herod (and Herod doesn’t really count because he was subservient to the Romans). Without sight to distract him, he is preserved to feel “the burnings of thy fathers, the former kings.” In other words, he can imagine his place in a long line of Jewish kings—from Saul down to him. Where does he fit in the big picture? How would the previous kings view his reign? Would he be remembered as the only king to lose everything the previous kings had fought to preserve? Indeed, wasn’t everything lost? Hadn’t the prophecies of Jeremiah been fulfilled to the last detail? What if things had been different? What if he had followed the advice of Jeremiah? What if he had cleansed Jerusalem of its idolatry and wickedness?

The “what ifs” must have burned a hole in Zedekiah soul. Ironic that his end would be full of burnings when we remember Jeremiah’s ministry started with a feeling “as a burning fire shut up in my bones,” (Jer 20:9) to raise a warning voice.

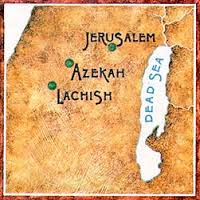

Jeremiah 34:7 all the cities of Judah that were left, against Lachish, and against Azekah

Hugh Nibley

About twenty-five miles southwest of Jerusalem in Lehi’s day lay the powerfully fortified city of Lachish, the strongest place in Judah outside of Jerusalem itself. Founded more than three thousand years before Christ, it was under Egyptian rule in the fourteenth century B.C. when the Khabiri (Hebrews) had just arrived. At that time, its king was charged with conspiring with the newcomers against his Egyptian master. A later king of Lachish fought against Joshua when the Israelites took the city about 1220 B.C. In a third phase, either David or Solomon fortified it strongly.

The city’s strategic importance down through the years is reflected in the Babylonian, Assyrian, Egyptian, and biblical records. These describe a succession of intrigues, betrayals, sieges, and disasters that make the city’s story a woefully typical Palestinian “idyll.” Its fall in the days of Jeremiah is dramatically recounted in a number of letters found there in 1935 and 1938. These original letters, actually written at Jeremiah’s time, turned up in the ruins of a guardhouse that stood at the main gate of the city—two letters a foot beneath the street paving in front of the guardhouse, and the other sixteen piled together below a stone bench set against the east wall. The wall had collapsed when a great bonfire was set against it from the outside.

The bonfire was probably set by the soldiers of Nebuchadnezzar because they wanted to bring down the wall, which enclosed the gate to the city.

Nebuchadnezzar had to take the city because it was the strongest fortress in Israel and lay astride the road to Egypt, controlling all of western Judah. Jeremiah tells us that it and another fortified place, Azekah, were the last to fall to the invaders. (See Jer. 34:7.) An ominous passage from Lachish Letter No. 4:12–13 reports that the writer could no longer see the signal-fires of Azekah—that means that Lachish itself was the last to go, beginning with the guardhouse in flames.

The letters survived the heat because they were written on potsherds.

They were written on potsherds because the usual papyrus was unobtainable.

It was unobtainable because the supply from Egypt was cut off.

The supply was cut off because of the war.” (“The Lachish Letters: Documents from Lehi’s Day,” Ensign, Dec. 1981, 48)

Reconstruction of the city of Lachish

Jeremiah 34:10 when all the princes, and all the people… had entered into the covenant… then they obeyed, and let them go

The narrative doesn’t tell us whose idea this was. Likely, it came from Jeremiah to Zedekiah although this is not expressly stated. In a rare case of doing good, the people, princes, and priests were gathered at the temple and all entered into a covenant before God that they would keep the judgment of the Mosaic Law which required the release of all servants. The Jews practiced a form of slavery but it was not the same institution of wickedness that plagued the United States of America before the Civil War. It was servitude, but the servants were generally treated well. Even then, the Lord had required all servants who were of Hebrew descent be freed after 6 years (Ex. 21:2-6). The seventh year was their sabbath, so to speak—a rest from the servitude of the preceding 6 years.

After 6 years of having your house cleaned and your animals cared for by a faithful servant, it would be hard to let them go, but the law was given to remind the Jews that no individual is greater than another in the sight of God, that all Jews were brothers. There was to be no justification for a caste system in Hebrew society. That was the ideal. Like so much of the Mosaic Law, this judgment was ignored.

Jeremiah 34:16 But ye turned and polluted my name, and caused every man… to return, and brought them into subjection

A week or two of cleaning the house and doing the dishes must have been too much for the indolent Jews. They were lazy, idolatrous, and disobedient. They had no problem with breaking the covenant made in the Temple before God and the priests as long as it meant they didn’t have to do their own laundry and prepare their own food.

Neal A. Maxwell

The selfish individual is often willing to break a covenant in order to fix an appetite. (Ensign, May 1999, 24)

Jeremiah 34:17 I proclaim a liberty for you, saith the Lord, to the sword, to the pestilence, and to the famine

Try to think of a time when God was sarcastic with his people. Almost never does the Lord use sarcasm, especially biting sarcasm, but this passage is an exception. The Lord says, “If you won’t keep your covenant to free your slaves, then I will proclaim a special liberty for you. You are free to choose which one you want: death by sword, death by pestilence, death by famine, or if none of those suit your fancy, you can go be slaves to the Babylonians for 70 years. Which sounds best? Take your pick!”

Jeremiah 34:18 when they cut the calf in twain, and passed between the parts thereof

Abraham asked God how he would know that God had given him the land for his inheritance. God commanded him to sacrifice a heifer, a goat, and a ram, dividing the animals in two pieces as if symbolic that God would divide the enemies of Abraham in two so that he might possess the land of his inheritance (Gen. 15). The act was a token of the covenant that God had made regarding the land.

It appears from this passage that the Jews followed this pattern when they made a covenant with the Lord in the Temple. As a token of the covenant that they would free their slaves, they divided a calf in two parts and walked between them. It was as if they had raised their arm to the square and said, “Yes.” When such an act occurs, the Lord takes notice and expects obedience.

Jeremiah 34:18-20 I will give the men that have transgressed my covenant… into the hand of their enemies

“Members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints often speak of the influence temple covenants and ordinances have in their lives. How might one who has not been to the temple best sense this influence? Elder Joseph Fielding Smith, President of the Church in the 1970s, wrote the following:

If we go into the temple we raise our hands and covenant that we will serve the Lord and observe his commandments and keep ourselves unspotted from the world. If we realize what we are doing, then the endowment will be a protection to us all our lives—a protection which a man who does not go to the temple does not have.

I have heard my father say that in the hour of trial, in the hour of temptation, he would think of the promises, the covenants that he made in the House of the Lord, and they were a protection to him. … This protection is what these ceremonies are for, in part. They save us now and exalt us hereafter, if we will honor them. I know that this protection is given for I, too, have realized it, as have thousands of others who have remembered their obligations

(Utah Genealogical and Historical Magazine, July 1930, p. 103).

(“Endowed with Covenants and Blessings,” Ensign, Feb. 1995, 40)

N. Eldon Tanner

Referring to these covenants in the temple, I would like to say to you again, remember these three words: keep the covenants. And I think I am safe in saying to you that if you and your families will keep these covenants, you will be happy, you will be successful, you will be respected, you will have good families that you can take back into the presence of our Heavenly Father. All you will have to do is remember three words: keep the covenants, the obligations that you have taken upon yourselves, the pledges that you have made. Keep the covenants. (Conference Report, October 1966, General Priesthood Meeting, 99)

John Taylor

God expects you to be true to your vows, to be true to yourselves, and to be true to your wives and children. If you become covenant breakers, you will be dealt with according to the laws of God. And the men presiding over you have no other alternative than to bring the covenant breaker to judgment. (The Gospel Kingdom: Selections from the Writings and Discourses of John Taylor, ed. by G. Homer Durham [Salt Lake City: Improvement Era, 1941], 285)